Gamification is a fancy word to describe the use of many different types of classroom activities. But what is it really? At its core, gamification in education refers to the use of game-like elements in non-game contexts to enhance learning. Teachers have always strived to find new ways to engage students, but how can teachers ensure that games are used appropriately to meet educational goals both inside and outside their classrooms?

With funds from an Erasmus+ grant awarded to my school, I had the opportunity last month to attend a course in Valencia, Spain on Game-Based Learning and Gamification in the Classroom. Along with teachers from six other European Union countries, including Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungry, Italy, Spain and Slovenia, I spent a week learning about the elements of game design and how to effectively integrate them into our educational framework.

With such a culturally diverse group, it was eye-opening to hear the different approaches teachers had to applying game-based learning in their classrooms. From analog games such as BrainBox, question-of-the-day and escape rooms to digital options such as Kahoot, Minecraft and AI image generation, we covered a wide variety of options. Aside from enjoying lots of tapas and empanadas, I was also able to visit Valencia’s impressive City of Arts and Sciences.

There are so many ways to incorporate games into a differentiated teaching strategy. The benefits are well-known: game-like activities can increase student motivation and engagement, provide real-time feedback, promote teamwork and collaborative learning, and allow adaptability to different types of learners. But teachers must also try to ensure that games are directly tied to learning objectives and that all students, not just the winners, have an enriching experience.

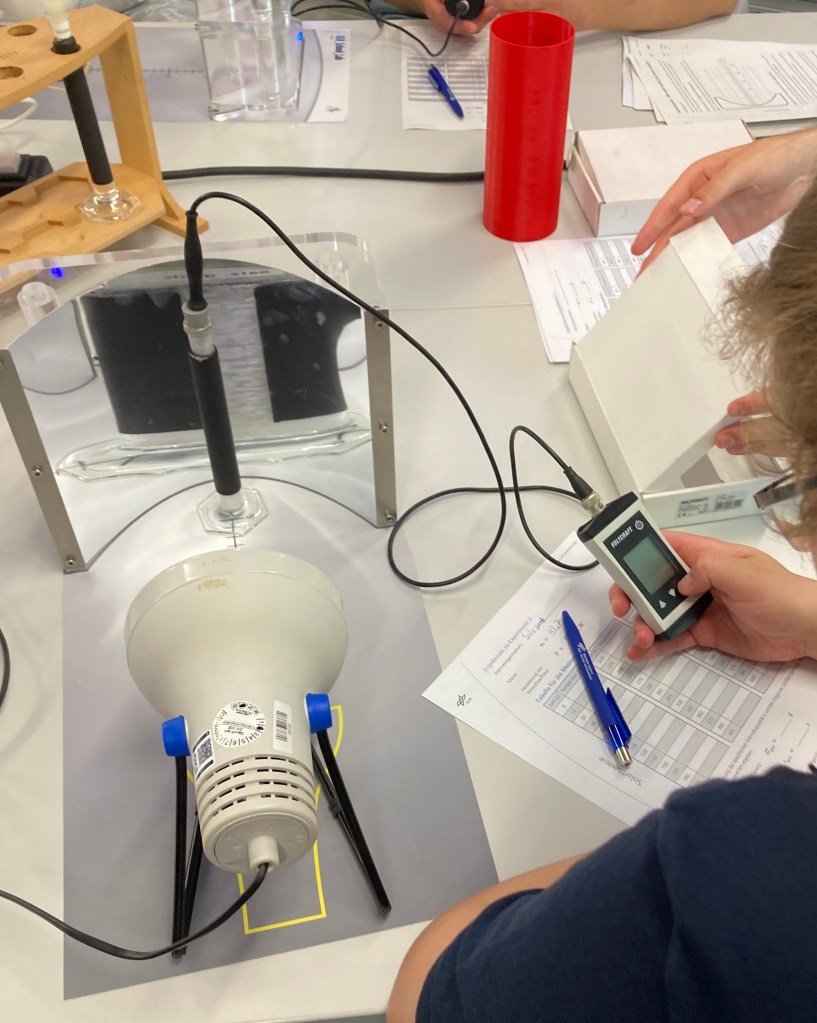

Everybody loves to play games, including my high school science students. In my physics classroom, I incorporate games to make learning more fun and to promote teamwork. I use games to introduce new topics and as a method to review material before quizzes or tests in order to reinforce important concepts and increase student confidence. In my experience gamification is a great way to enhance student learning that provides an immersive method for delivering science content.

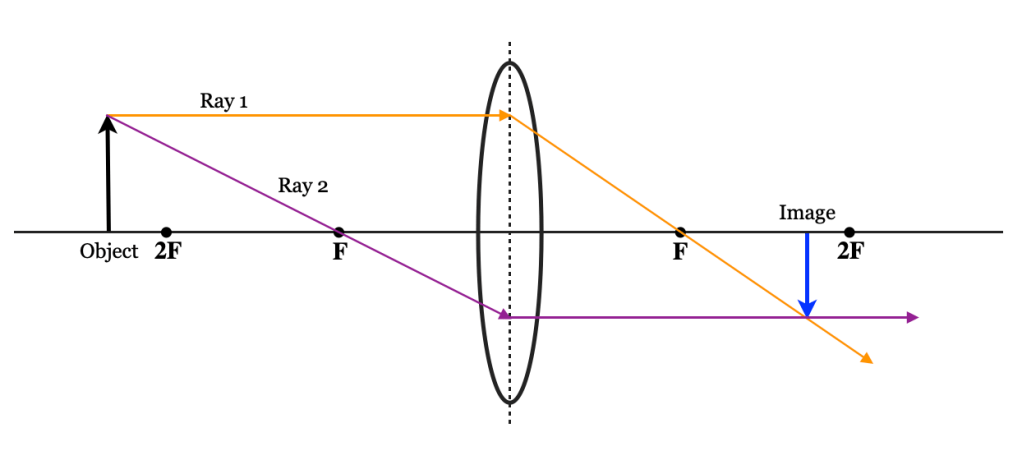

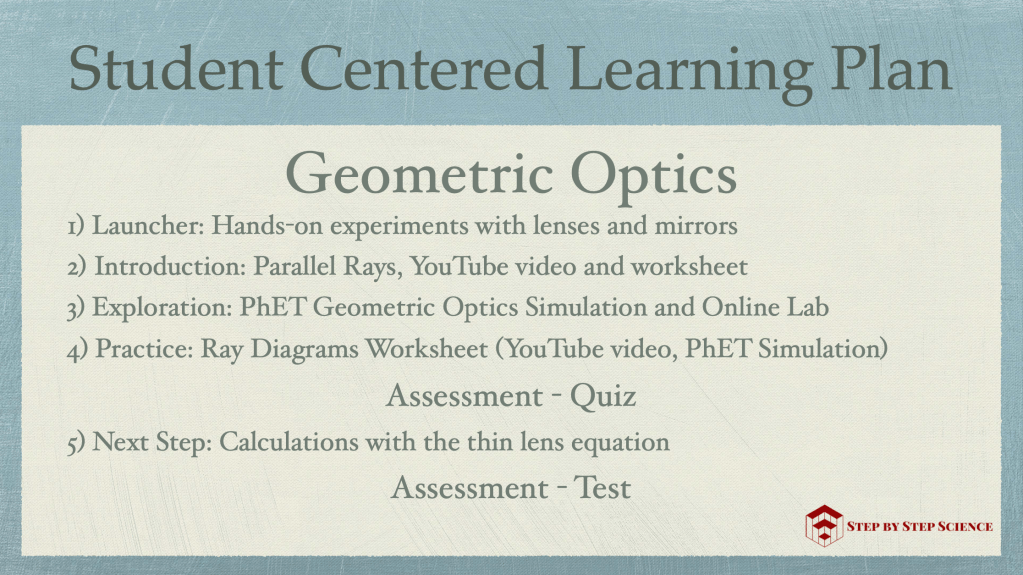

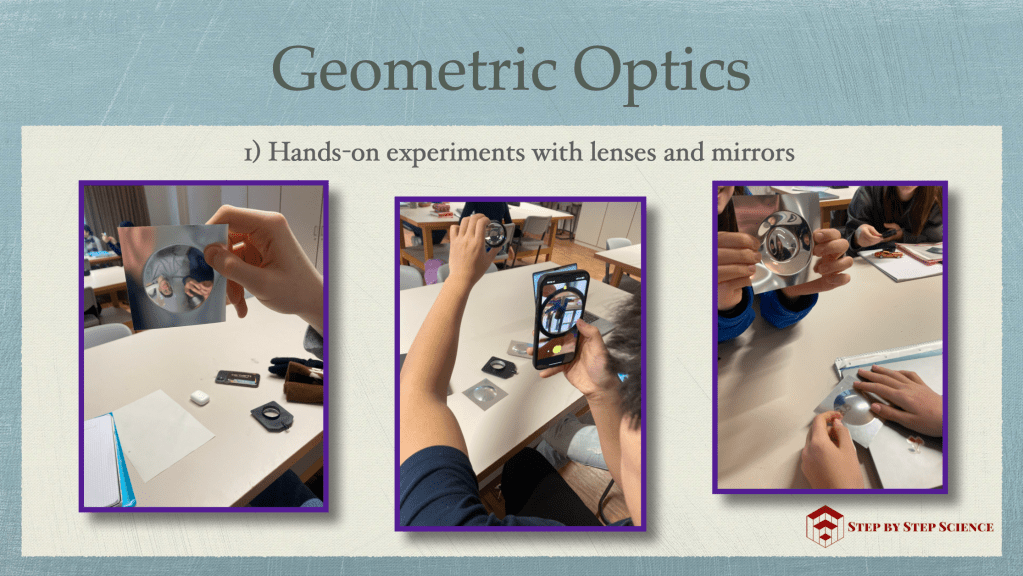

Before our 10th grade lenses and mirrors test, the students play one of my most popular games called Name that Image. With the help of the Geometric Optics simulation from PhET Interactive Simulations, the location of an object is first projected at the front of the room. Students working in small groups must determine the characteristics of the image that will be produced based on whether the light rays have been refracted through a lens or reflected off a mirror. Teams are awarded points based on the accuracy and completeness of their answers.

I also like to incorporate non-digital games like matching and sorting cards. For example, in the Motion Graph Matching game, student groups must correctly sort position vs. time, velocity vs. time, and acceleration vs. time graphs to fit the description of a specific motion scenario. It’s fun to wander around the classroom and watch students “argue” about which graphs belong together. This is a great way for them to collaboratively deepen their understanding of motion and graph interpretation.

For a more extended and hands-on challenge, I run a rubber band race car project, where students build a vehicle and compete to see whose car travels the farthest. Points are awarded based on specific design criteria and the distance the car travels, adding a competitive edge that motivates them to apply physics principles creatively. Here’s a video that shows how to make a rubber band powered car: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YS4YDFMogJo

Whether developing new games or adapting older material to be used in gamifying your instruction, the possibilities are endless. Overall, gamification in my classroom enhances student engagement and makes complex topics more accessible and fun. When games are properly embedded into course learning goals, they have the potential to be a valuable component of almost any educator’s toolbox.